The late Carl Ginsburg, a legendary Feldenkreis practitioner, and a gentleman, gave me permission to place this story online. It was published in his short book Medicine Journeys. The “Todd-Ashbys” are the “Adies.”

George and Helen Adie are the Mr. and Mrs. Todd-Ashby of Carl Ginsburg’s Medicine Stories, Center Press, Santa Fe, 1991, “The Daphne Blossom”, pp. 55-9, he kindly gave me permission to post it.

THE DAPHNE BLOSSOM

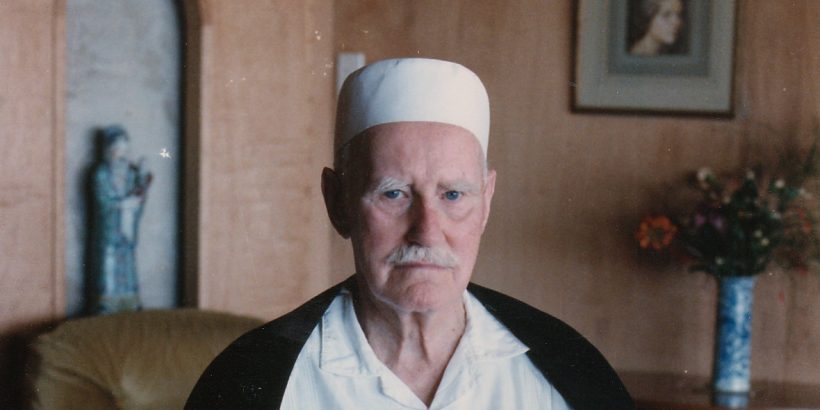

Mr. Todd-Ashby appeared at the door, tall and solid in a long dressing gown and white cylindrical fez. He was an astonishing eighty-six years old, considering he had lived the last third of a century missing his right lung, and with the other lung working at two-thirds capacity. He greeted us warmly and we followed him into the house.

The bush was in flower. Early spring. From Mr. Ashby’s window you overlooked the thick bush of shrubs and gum trees on its descent down to the beach. The ocean beyond was rough a heavy surf breaking some distance from the sand.

Adele and I had driven up through French’s Forest, past Narrabeen and Mona Vale. After the turn off to Bungin Beach we were on the peninsula with the Pittwater to the west and the Pacific on the east. We had to drive up a narrow road that snaked between tall eucalyptus. A sudden squall with a fine but heavy rain broke as we got out of the car.

I had met Mr. Ashby two years before. He was having difficulty swallowing, a condition apparently related to the operation to remove his lung. Adele rang me up and insisted I see him. “He’s very bright and lively,” she said, “in spite of his condition. I’ve been his doctor for a number of years now. He’s really very lovely to work with.” Her voice was seductive with its lilt and tiny musical lift at the end of each sentence.

“What can I do in one go?” I said. “I’m leaving for the States in two days.”

“Oh, you’ll think of something,” she said. “I know you can help him.” Adele had more faith in my abilities than I had in myself.

Mr. Ashby barely had the strength to get up the stairs at the flat where I was staying. Despite this, I noticed that he had a lively energy. We spoke very briefly. He then lay on his back on the low table I used for lessons at the flat and literally put himself in my hands. For my part I quickly observed his situation. The right side of his chest and the compensating twist in his neck resulted in a pressure on his throat which prevented his swallowing. I saw a need to expand his ribs on his right side. But how?

A very rapid reasoning resulted in an assessment: even if his lung had been removed, he still had the muscles in his chest. It was obvious, however, that he didn’t use them. I decided that it must be his knowledge of the fact of his missing lung that led to his collapsing his chest. What he needed, I thought to myself, was a lung, an imaginary lung. I even had a process in mind.

It was a gamble to expect Mr. Ashby to accept the strange exercise I was to propose to him. I was sure he would question it. The one thing I knew of his background was that he had been a well known-architect in London before he retired to the bush. However, the exercise went beautifully. I had Mr. Ashby explore the good lung as if it moved from the inside. When he was clear as to the nature of the movement, I had him imagine a right lung that moved in the same way. His chest immediately began to expand.

“Very clever,” he said to me afterwards. “I think I’ll enjoy working with your method. It certainly made a difference to me.” Adele called me three or four times in the intervening two years to tell me of Mr. Ashby’s continuing improvement. I was pleased about his progress, but was even more astonished at his remarkable intelligence and perceptiveness. He understood completely that we had made a successful fiction together. He knew how to use that fiction totally to his advantage, and it took only one single session.

Now Mr. Ashby was undergoing a new crisis. Adele suggested we see him at his home. This time he had apparently pulled a ligament between his rib and the connecting vertebra.

His pain was very apparent in his attempt to move ever so carefully and avoid bending or twisting. Despite his pain and labored breathing, he was cheerful and talkative. His words came in short, puffy breaths as he led us to his bedroom.

Adele said, “Mr. Ashby has designed this room for himself. You must see his bed. You can raise the bottom half or the top. Mr. Ashby has designed these special pegs for the purpose, which fit into different holes to create different heights.” The bed not only adjusted, but Mr. Ashby had designed a swivel arrangement with a hook that allowed the bed to be wheeled into different positions while also staying attached to the wall As interesting as I found the bed, I was even more attentive to the two framed photographs above it. These were both of Mr. Gurdjieff. One which I had seen before showed Mr G. looking fierce with his bald head, penetrating eyes, and turned up moustache. In the other he was smiling, wearing a fez and showing an unexpected sweetness in his face.

I peered into the adjacent part of the room. There was an English oak Chippendale desk over which hung two more photographs of Mr. Gurdjieff. One of these taken in Paris in his last year showed him fully erect and present, eating his dinner. To either side of these were two photographs of Madame de Salzmann. On top of the desk sat a small gold Buddha, perhaps Burmese or Thai.

Mr. Ashby sat down on his bed and invited us to bring chairs and sit for a moment.

“Did you know Mr. Gurdjieff personally?” I asked.

“Ah, yes,” he said. “I was fortunate to have been one of his pupils. An extraordinary man.” He paused to catch his breath. “I have a group here, you know. I have been teaching his work for years.”

“Were you at Fontainebleau?” I asked.

“No, no. I met Gurdjieff much later, in his last years in Paris, just after the war. He was at the height of his powers.” Although Mr. Ashby was audibly making short and distinct gasps as he spoke, his voice was steady and clear.

Adele watched as I gave Ashby his lesson. This time I worked without words. It was my hands that spoke. I asked him to lie on the bed on his side and placed a pillow under his head to make him comfortable. By placing one of my hands on his lower ribs and the other on his hip I could gently remind him how his ribs moved, how indeed he could allow more movement differentially and subtly between his chest and hips, chest and shoulders.

He did feel immediate relief afterwards. Slowly, he got himself up from the bed. I asked him to walk about a bit and feel the differences in himself. This he did with ease.

He then left us a short while to order some coffee and cookies for us. Somewhere in the other part of the house there were servants and Mrs. Ashby. I was to meet her on my next visit a week later, when I gave lessons to both Mr. and Mrs. Ashby, and was served a dinner of caviar stuffed into avocado halves, washed down with a glass of Armagnac. Mrs. Ashby was a small tidy woman who was equally a devotee of Gurdjieff.

She had accompanied Mr. Ashby all over the world in his pursuit of teachers. In fact it was an accident in the jungles of Venezuela while visiting a Gurdjieff community that led to her injuring her leg. Now that she had limped about for twenty years, she wanted me to help her walk more easily.

She too was an apt pupil. With each move I made with my hands to connect with her, I detected an immediate response.

As I guided her to feel how she could freely use her healthy uninjured leg, I could see how her keen awareness of herself led her to an understanding of what I was asking of her. And indeed when she stood up after the lesson, one could see that she now knew how to place her weight more evenly on her legs. Her walking too was visibly easier and more confident.

As we waited for the coffee and cookies, Mr. Ashby took me aside to tell me something special. Adele left to speak with Mrs. Ashby. “As I don’t generally tell anyone about this,” Mr. Ashby said, “these words are for you and you alone.”

I understood then that I was to receive a gift, and I took his admonition seriously. Mr. Ashby spoke first about pain, his own first, and, more generally, everyone’s. Pain was a part of life and everything in life was worth attending to. He, meaning himself or Mr. Gurdjieff, learned from pain, and therefore it was of no more consequence than anything else.

Mr. Ashby then related a story about Mr. Gurdjieff. It was about Mr. G. and a wrench that Mr. Gurdjieff had used with extraordinary force. Mr. Ashby described how Mr. G. placed that wrench back on a table. He reproduced the gesture for me with his own hand. It was exquisite. Mr. Ashby repeated it three more times. The powerful force of using the wrench dissolved into a movement of such grace, such delicacy that I can still see it, still feel it as some after-image in my own musculature.

Adele returned with the refreshments. We chatted lightly. I felt a need to be alone a moment. I wandered into the living room. Near the doorway, the lower ceiling was cut away in a large oval and I therefore stood under a very deep blue recess in the oval space. It was like standing under a night sky. I watched the ocean and the heavy clouds which rolled in. A large black bird with a long and slightly curved beak perched on the outer window sill. He had a yellow circle about his eye. We watched each other for what seemed a long time. He flew off as Adele fetched me for the return journey.

It was dusk. The rain had stopped. Adele said, “Just look. All the Daphne blossoms. I’ll get you one.” She walked to the end of the drive and picked a large blossom. She returned to the car.

“It has such a lovely aroma,” she said.

The fragrance was intense. It permeates my memory of the drive back. I thought again and again of the gesture that Gurdjieff had used and Mr. Ashby had duplicated for me. I saw in it the essence of what I know in my hands, that utter delicacy that I learned from my own teacher, Feldenkrais. I saw too that it was the innocence and openness of that gesture, its freedom from any thought, any preconceived constraint, its purity of intention, that led to its possibility. And that possibility is the possibility of the heart. This was Mr. Ashby’s gift to me.

Rest in light and peace, Carl, you related your medicine journey with style.

Beautiful memory! Thank you for sharing this Joseph.