At the basis of the practical methods brought by Gurdjieff, are the work with sensation and feeling. In the masterful talk “Now I am sitting here …” he gives perfectly clear of them. Can we say anything more general? After all, if I asked you what an “animal” was and you responded “a duck, a goose, a lion,” and this is how in fact we learn what animals are. We see example after example, and we somehow abstract from the examples an understanding which allows us to say, when we see a rhinoceros that it, too, is an animal. The number of doubtful cases, such as insect eating plants are too few to disturb us.

Likewise, we quickly come to accept that the instinctive sensations, such as that of breathing and blood flow, are indeed sensations. But with feeling it is not always so simple. Part of the problem is that I can always come directly to sensation by touching a part of my body. But that cannot be done with feeling. Also, there are many instances where one is not sure whether one is experiencing feeling or sensation or both. Thus, when we work with Gurdjieff’s methods for releasing tension from the face, people often both sense and feel a sort of softness and gentleness in the face. Clearly, there is some sort of overlap between sensation and feeling.

My own idea is that, in practice, I can distinguish the two of them, and come to them speedily enough for any purpose I have ever had. But, with feeling, the thing is that often I come to what I can only call the “raw material” of feeling, although it is more like a localised subtle gathering of forces than a lump of iron ore. I cannot always say that I am experiencing this feeling or that feeling, but the energy of feeling is there. And why should that not be enough for my aims?

So, for feeling, we are blessed just to be able to experience the force of feeling. It is always good, always positive, always life affirming – even if subtly so. Yet, I wish to understand ever more about the laws of world-creation and –maintenance. The material in Gurdjieff’s and Ouspensky’s books are wonderful: it points me to the centres with which the sensation and feeling are associated. That is a great help. Using this knowledge can help me deepen my experience of both.

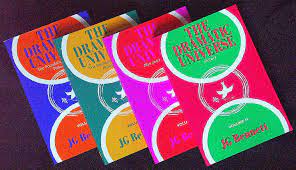

I am now working through Bennett’s Dramatic Universe, and am, once more, impressed by what I am finding. In volume 3, section 15,39.4.2, Bennett speaks about “The Element of Function” in us. He describes human function in “the material structure relevant to him that is, his physical body” (132). He notes that the limbs and organs all have “well-defined functions” which influence our “awareness of the present moment” (132). These diverse influences suggest that our functions can be described in three classes: material, vital and psychic. With extraordinary precision, he states: “The material functions consists, firstly, in providing a quasi-rigid yet flexible and adaptable structure associated with the present moment of awareness” (132). These are all the bodily parts and systems, muscles, nerves, and metabolic and respiratory systems, etc. These are related to and depend upon the bio-chemical systems. All this is what we study in anatomy, physiology, bio-physics, and bio-chemistry. These depend upon various energies. Bennett here refers to energies E12 to E7 in his system. I shall not pursue those here, but they are dealt with more fully in volume 2 of the Dramatic Universe, and in the book Energies.

These functions are integrated, by the organic whole, to serve the whole by being organised into the “three main types of psychic function that are experienced in the mind” (132). I think Bennett has hit upon something critical here: the various functions represent the transformation of energies through differentiated members and organs of the bodies, as experienced in our consciousness. The process begins with automatic (self-moving) transformations, but it does not end there: it reaches to consciousness. The thing Gurdjieff is exploring, as I see it, is the interaction between these automatic and conscious aspects, and the extent to which conscious action for a conscious aim can obtain, from the energies, better and more balanced functions, and the formation of higher being bodies.

Bennett identifies the following functions which use our bodily mechanism: inner sensation of the vital processes; outer sensation of perceptions, movements, and touch; feelings of emotions of like and dislike, desire and aversion; thoughts of mental images and signs, traces and memories, and expectations; and sex which represents the connection between two bodies and minds (133).

I also think he is correct to state that these functions are “coordinated by brains or centres of functions that are connected with the nervous system, the blood and the organs of perception and action” (133) Note the role of the blood, but in addition, the organs of perception and action have roles for all the functions we reviewed in the above paragraph.

As stated, Bennett’s insight is that “each of the functions has the power to produce ‘states of mind’ (133), to which he adds that the connections between the functions of sensation, emotion, and thought with the mind are our human powers. What I find odd is that he then says that “sensation has the power to produce the experience of presence,” and “feeling has the power to produce the experience of force” (133) It is not that this is wrong, but that the attributes could also be swapped: surely sensation has the power to produce the experience of force, and feeling to produce that of presence.

I think the question is how do sensation and feeling contribute to both the experience of force and that of presence? I think they complement each other. And how is it that the centres are then subdivided into positive and negative, and into further subdivisions?

Now, I think that Bennett is entirely correct to say that “Thought has the power to go outside the present moment by connecting us with perceptions, traces or memories, expectations and mental images. These functional activities collectively give the power of direction” (133).

So, although it is not so much as I disagree with Bennett as that I have what I think is a fundamental question, his exploration of these questions is important and matchless. I suspect that we will study this further through conscious experience, not through the observation of lab rats. Engaging with Bennett’s thought is, in its own way, quite exciting, even if we do not have minds like his. I don’t think the mind is the point: it is the conscious engagement.