Many years have passed since I first heard it, and only now have I come to grips with the Walls and Bridges album. For no other Lennon record has it taken so long for them to open their mysteries. I can see now that even in that puzzling fact lies the secret of Walls and Bridges. Finally, however, all my diverse thoughts and feelings have come together, as it were, and I am quite confident in saying that this is a brilliant album, marred only by two tracks (“Going down on Love” and “Beef Jerky”) and one joke (“Ya Ya”).

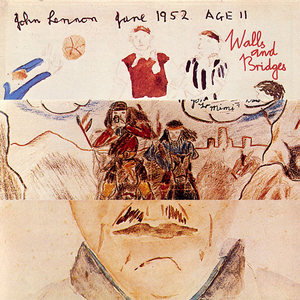

The key to this record has been hiding in plain sight: it is an album of walls AND bridges. That is, it is an album of opposites and complements. Our word album comes from a Latin root meaning white, as in the alb which the priest wears beneath his cope. It means a “white book,” or a “blank book.” And so it came to mean a book of blank pages into which you paste diverse pictures, and then, from about 1909, a collection of tracks on one or more records. And this explains the cover as it originally appeared: one third of three entirely pictures, one above the other, making for a disorienting experience.

But while the word album captures the seemingly random order of the songs on Walls and Bridges, it does not quite do justice to the way that it was all blended together by the lyric guitar playing of Jesse Ed Davis. In fact, if the content of the lyrics was to do with connection and separation in human relationships, the atmosphere of the whole was defined by the sensitivity, almost hypersensitivity of Davis’s virtuoso playing, with its moments of howling (“Scared”), exuberance (“Surprise, Surprise”) and lyric grace (“Old Dirt Road”).

On this album, two opposite scenes, dark and light, have been laid side by side, mosaic fashion. In fact, it is an album of contradictions: it is alright and it isn’t alright, says Lennon. I am sad, and I am happy. I am scared, and I am surprised by delight.

This also explains why it was greeted with a muted acclaim at the time, but has been better thought of in retrospect: people expected and wanted a strident statement. Even if they had not liked it, for the most didactic of his records, Some Time in New York City is, with one exception (“New York City”), unlistenable. Everyone thought they would get a clear statement, rather, they received ambiguity and co-existence of opposites. Therefore, the record was criticised as being a patch-work.

Rather than producing something like Imagine, a straightforward “we’re going to change the world” record, Lennon had, for the first since the Beatles had discovered Dylan, produced a collection of songs which dealt with nothing but personal relationships, and the emotions of love, regret, hatred and friendship. However, it did so deeply, and, in addition, Lennon employed a variety of musical modes and fashions, with great success: from the roaring “What you Got” to the laid-back collaboration with Harry Nilsson “Old Dirt Road.” As Lennon said to May Pang: “… this is … the fastest, easiest album I’ve ever made …” (Loving John, 228); and that was due to the professionalism he brought to the recording, and his mastery of his art.

For me, the stand out track is “#9 Dream,” which I dealt with pretty extensively in my book on John Lennon. This, together with “Whatever Gets you,” “Old Dirt Road,” “Bless You” and “Surprise, Surprise” are the four songs of positive emotion, which balance the songs of sadness and hatred: “Going Down,” “Scared,” “Steel and Glass” and “Nobody Loves you when you’re down and out.”

If “#9 Dream” is the standout trip, yet “What you Got” is a worthy second. The energy leaps out from the speakers, and Lennon’s delivery is raw and heartfelt. I think it is one of the greatest performances of his career up there with “God” from the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. But I couldn’t really take that in, until I recently realised what he meant when he was saying: “Don’t want to be a drag, everybody got a bag. I know you know about the Emperor’s clothes.” And what I think he means is this: “I am the emperor who has no clothes, but is forever being told how well dressed he is. I hope that isn’t too depressing, because I know that you all have your own problems and issues to deal with.”

In fact, it was the revelation that he was saying that he himself is living a pretence in full public sight that prompted me to listen to this album again, many times, and to write this now. “What you Got” is one of the under-rated masterpieces of rock and roll. Lennon took the O’Jays “For the Love of Money,” a great song, but turned it into something I, at least, find more direct and therefore more powerful. It is also ambiguous or, more precisely, tells two different stories at the same time. On one hand, he has lost Yoko, and he only now realises what that amounts to. On the other hand, however, “you gotta hang on in, you got cut the string.” The string must be the chain which bound him to her.

On the one record, he says goodbye to Yoko and hello to May Pang, but he also declares that he will forever love Yoko in one of the most poignant songs of lost love imaginable: “Bless You.”

Another quite unique song is “Old Dirt Road,” the only recorded song attributed to both Lennon and Nilsson as songwriters. It does not boast a gripping melody: it is something that you need to sit back and listen to, but it repays the effort. The road in the song is quite clearly life. That jumps out at us straight away. The “human being lazy-boning out in the hay: stands for “Everyman,” that is, for each of us. The main difficulty with the song is the obscurity of some of the lines such as “It’s better than a mudslide, mama, when the dry spell come.” It takes a while to realise that it is an example of seeing the bright side of any situation, because dry spells never cause mudslides. But the whole song is transfigured by Davis’s evocative guitar lines, and the ending more than adequately sums it up, as Lennon repeats, consolingly, “Keep on keeping on. Keep on keeping on … So long … so long … bye, bye, keep on keeping on.”

That song could well have been the final track on Milk and Honey. It would have been a fitting and philosophical close to the most glorious and consistent career in modern music.

Joseph Azize, 9 August 2017

Curious what you think of the Menlove Ave. album released by Yoko in 1986. Side one is one unreleased Lennon-Spector original, three outtakes from Rock’n’Roll album, and an outtake from Mind Games. Side two is five songs from Walls and Bridges in far superior stripped down versions of just John, Jesse Ed Davis, and bass and drums. Recorded early July 1974 just prior to actually setting down the tracks. To me, the whole album is like Lennon’s Dark Night of the Soul. Final song is Bless You.

I believe it depends on the country you live in, so you will have to search on-line. Enter the title, and it will come up.